By VICKY EIBEN Presented at “Lands of the Living: An International Sympoisum on the Internationl Influence of N.F.S. Grundtivig” at the University of London, August 2-3. 2018 Reprinted from Grundtvig-Studier 2018, eds. Mark Bradshaw Bsbee and Anders Holm, København, 2018, 96-99. After visiting Highlander Folk School, Eiben committed herself to building understanding about Grundtvig and the folk school movement in the United States. She became a founding board member of Driftless Folk School in Wisconsin. In 2018, she organized the first-ever Upper Midwest Folk School Gathering, and she now works in a teacher preparation program at Viterbo University. The ideas of N.F.S. Grundtivig travled to the United States with Danish immigrants in three waves of folk school development. The first was in the late 1800s when six schools were established. Two of those orginal schools remain today: Danebod in Minnesota and Ashland Folk School in Michigan. Danebod offers programming during the summer; the folk school spirit is very much alive there in the singing, discussion, dancing, crafts, and fellowship. Ashland, now Circle Pines, has a strong social justice orientation. The second wave of folks schools swept the USA in the 1920s. Olive Campbell and Marguerite Butler spent two years visiting folk schools in Scandinavia and, in collaboration with the people of Brasstown, North Carolina, they founded John C. Campbell Folk School in 1925. They applied Grundtvig’s idea that people would be enlightened not by Greek and Latin but by studying their own literature, lore, craft, and economy. Jens Jensen was born in Denmark and brought his understanding of folk schools with him when he immigrated to the U.S. In 1935, he established The Clearing in Ellison Bay, Wisconsin. He called The Clearing “a school for the soil,” believing that soil is a metaphor for regional ecology and culture, which is the basis of self-knowledge, clear thinking, and responsible citizenship. Today, The Clearing offers classes in nature studies, creative writing, fine and folk arts, history and philosophy. Myles Horton became aware of Ashland Folk School in the 1930s, and then he spent a year in Denmark. He wanted non-formal adult education to contribute to change in America. He listened deeply to the desires and needs of people in Tennessee and he was compelled to found Highlander Folk School. Since its inception, Highlander has served as a catalyst for grassroots organizing and movement building, particularly in the U.S. Civil Rights movement. Stories from three schools offer insights into the varied ways that Grundtvig’s philosophy and the Danish model inspired third wave initiatives. In 1998, a group in Washington County, Maine, began a community-based research project on education. They wanted to know “what models of education have led to sustained and substantial positive social change.” The group attended a workship on how to start a folk school, led by Jacob Earle from Denmark and Hubert Sapp, former director of Highlander. Cobscook Community Learning Center (CCLC) emerged from this process with the mission: “To create responsive educational opportunities that strengthen personal, community, and global well-being.” CCLC is a hub of educational opportunity and offers a variety of courses, social and art events, and activities and programs initiated by community members. Collaborations have resulted in an alternative high school, programming for at-risk youth and public-school support, and an intervention system called Rural Turn-Around for Children. Their work fills a critical social and educational niche. Director, Alan Furth, emphasized, “By taking care of the spirits and hearts of individuals, we will ultimately have a healthier, safer, and more respectful society.” Ultimately, they would like to work at the political level to make this type of social infrastructure available in other communities, as it is with Scandinavian folk schools. North House Folk School (NHFS) lies on the north shore of Lake Superior in the town of Grand Marias, Minnesota. In 1997, Mark Hanson, a local boatbuilder, was asked to teach a month-long kayak-building class as part of community education, and the experience ignited a vision. Mark had grown up spending a great deal of time with his grandfather who was a strong Grundtvigian. He remembered his grandfather saying that Grundtvig believed schools were needed that supported the holistic development of rural people. Mark believed that the philosophy and approach of Scandinavian folk schools would be an ideal fit for Grand Marais. Today, the school has six buildings, a large sailboat, works with 140 instructors a year in a variety of courses, and also offers programming for public schools. In 2016, NHFS brought $10.6 million into the local economy. North House exists today because of Mark’s relationship with his Grundtvigian grandfather. We hear traces of Grundtvig in a quote from Director Greg Wright: “When you start to get to know a landscape or when you begin to use your hands, you’re digging into the guts of what it is to be human. . . . We are trying to connect the past, the present, and the future together to make sure life stories are rich and so is our perspective on what makes us human.” The founders of Driftless Folk School near La Farge, Wisconsin were inspired by experiences at North House, John C. Campbell, and Highlander. They desired to build on the rural, agricutlural heritage of the area as well as the heritage of immigrants and Indigenous Peoples and the geological and natural history of the region. Courses and events are offered on local farms, in the homes and studios of local residents, and at a newly developing campus. A wide variety of classes are offered such as blacksmithing, stargazing, folk dancing, herb gathering, and traditional homesteading skills. Program Director Mark Sandberg reflected, “As humans, for so much of our history, learning has been from one another . . . how to make tools, build homes, secure and preserve food, read the sky, and make the very clothes we wear. Folk schools help re-establish this connection to our rich human heritage. In the fast-paced world in which we live where disconnections are common, to feel human and connected to our environment, ourselves, and one another is welcome.” Schools in the U.S. share a number of beliefs that are part of Grundtvigian thought and the Danish folk schools for life: Learning is a lifelong; oral culture/the living word is central; schools are responsive to the needs and struggles of ordinary people; wisdom of ordinary people is valued; learning is hands-on and experiential; learning is non-competitive and emphasizes local culture; learning takes place within community; human identity is at the core of education; and education is local, decentralized, and originates from local people. [email protected]

0 Comments

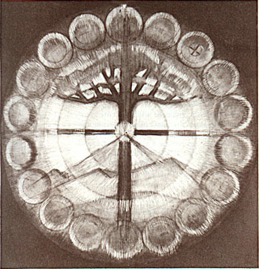

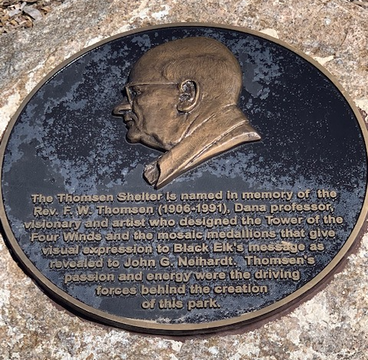

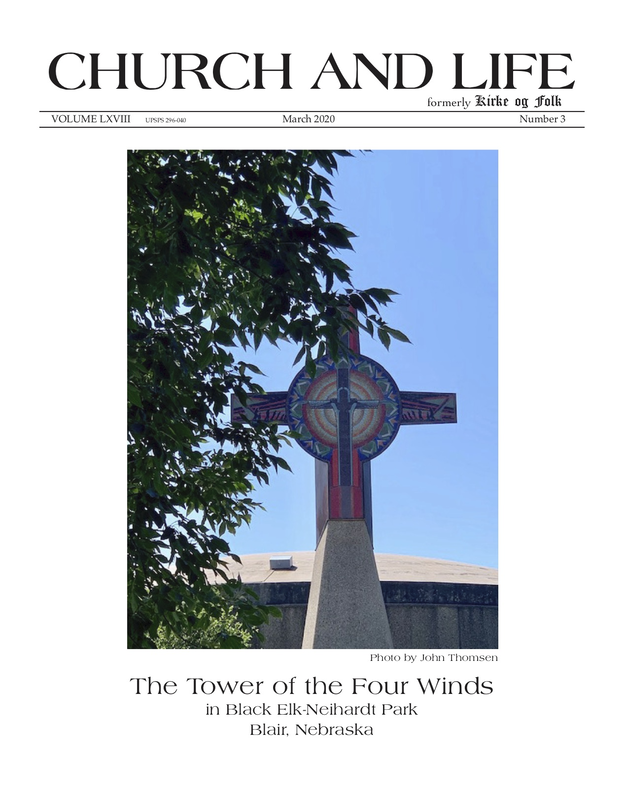

The tree of life flowering within the sacred circle at the center of the earth.  From a speech delivered August 4, 2013 at the opening of the F. W. Thomsen permanent art exhibit at the John G. Neihardt Center, Bancroft, Nebraska By JOHN THOMSEN Dad would have been greatly honored to know that his work has found a home at the Neihardt Center next to two of the men he admired the most: John Niehardt and Black Elk. . . . In 1955, Dad was asked to teach at Dana College full-time as the head of a growing art department. Because of Dana’s lack of funds, Dad was [also] asked . . . to take on the demanding position of dean of men. This was during a time when some of the students had just returned from Korea and were suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder; so on top of the regular duties of a dean of men, Dad spent many hours counseling these young men who would often wake up shaking from horrible nightmares. I think that this kind of passion for what is healing and good and meaningful is what eventually brought Black Elk, Niehardt, and Dad together. . . . Luckily Dad never believed that God could be put into a little box called Lutheranism, Catholicism, or any other ism, so when he was about sixty-five, around 1970, and discovered Black Elk Speaks, he was blown away by the power of the vision and beauty of the symbolism. . . . Niehardt was impressed by Dad’s feeling for the symbolism of Black Elk Speaks . . . [One} of Dad’s works that particularly excited Niehardt was The Star of Understanding, the morning star. Dad talked to Neihardt about [M]an being what he is all over the world, pretty much the same in nature and impluse, and the universe being the same; the sun rises and sets [as do] the moon and the stars and most people have some kind of admiration for the morning star. Niehardt responded [with a quote from Black Elk Speaks], “Then the daybreak star was rising, and the voice said ‘It shall be a relative to them, and who shall see it shall see much more, and those who do not see it shall be dark.’ ” . . . Then Dad showed Niehardt colored photos of a very large pastel of the Tower of the Four Winds, and Niehardt immediately noticed that both colors red and black are shown on the horizontal arm of the cross and that they then become vertical as they work together. Dad said, “Yes, they merge.” And Niehardt replied, “They merge and then you have the tree of life.” Dad mentioned that all he needed was Niehardt’s blessing on his conception for the Tower, and Niehardt said with great sincerity, “Well, boy, I believe it, and I believe in that. I think it’s a wonderful conception. The idea then — they have been horizontal, but they rise.” Dad said, “Yes. Now it’s lifted right up.” And Neihardt replied, “Yes, both; both of them will be lifted up. And then they join together, and you get the tree of life. . . . .Oh, it’s gorgeous; it’s just gorgeous!” What a feeling Dad must have had when he heard those words. Niehardt had given him his blessing, which Dad felt he needed to move ahead with the Tower. . . . Since the 1950s, Dad had had a vision of a cross near the top of Dana Hill that would be seen by travelers as far as the distant bluffs on the other side of the Missouri River Valley. Dad tried to find backing for this dream, but it was not to be. But dreams like this have a way of working out in mysterious ways, and of course The Tower of the Four Winds was the magnificent result. One thing about Dad, he did not have to have something this important happen quickly. Someone once said to me, “Your father is like moving water, continously moving and moving and wearing down everything in its path.” And it was true. If there was something worthwhile, Dad wouldn’t stop and with the Tower, he was truly inspired to continue working diligently. Moving, moving, moving . . . believing, believing, overcoming one obstacle after another, and continuing to move until the Tower, the park, and the fine artwork depicting some of Black Elk’s tremendous visions had been accomplished. Dad was fortunate. God had chosen him to spearhead this mission, knowing that the realization of these goals could not be controlled by Man but would happen in God’s own time. I particularly want to mention one of Dad’s later works, called Peace. It’s a work he loved very much because, in a powerfully symbolic way, it holds so much of Black Elk’s vision. I often regret Dad didn’t live long enough to turn this small pastel into a monumental mosaic or radiant stained-glass window. . . . This beautiful pastel comes from these powerful words in Black Elk Speaks: Then I was standing on the highest mountain of them all, and round beneath me was the whole loop of the world. And while I stood there I saw more than I can tell, and I understood more than I saw. . . . Black Elk, Neihardt, Dad — men chosen by God to spread His truth and His light. I feel great joy that these three fine men came together through spirit to give us such images, thoughts, and feelings of spiritual power. [email protected] |

Editor InformationBridget Lois Jensen Archives

March 2023

|

Subscribe | Gift |

Submit an Article |

Contact |

© COPYRIGHT 2019 CHURCH AND LIFE.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed