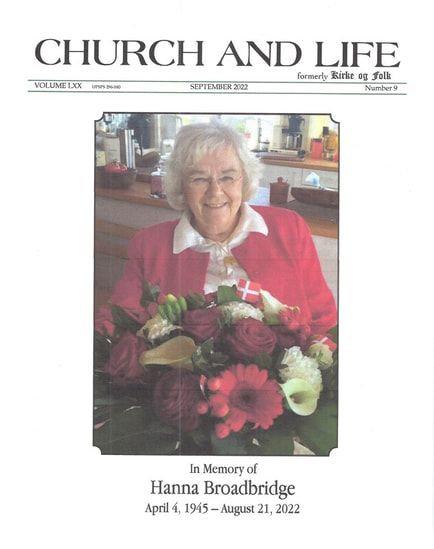

As the cover indicates, our dear Danish correspondent Hanna Broadbridge has died, so this issue is dedicated to her memory. Her husband emailed the bulletin of her memorial service, which included the song, “Tænk, at livet koster livet,” and its English translation, “Life is what we pay for living.” The text is a poem by Jørgen Gustava Brandt. The Danish Songbook uses music composed by Ole Schmidt, but there is also another popular melody by Bent Fabricius Bjerre. Both versions have been shared as YouTube videos on the Church and Life website as one of the published articles for this month. The poem’s sentiment echoes in the two articles that pertain to the Danebod Fall Folk Meeting. Mary Ann Doyle shares her appreciation for the meeting in “Tending to Life” as she anticipates returning after her first experience in 2019. Karen Wells reflects on a couple of presentations from this year’s meeting in “Stimulating Growth.” The final offering we have from Hanna Broadbridge. “What is the Point of Food Banks?” is very appropriate as it reflects the open embrace that she had for everyone, especially people on the margins of society. Hanna spent decades in lay leadership positions in the church, but, as we hear from Pastor Andrés Albertsen in “What Is It to Be Christian?,” Hanna’s or anyone’s Christianity is in, as Kierkegaard would say, the life that is lived, not the structure of an institution. Just as Kierkegaard was a critic of the church, Viggo Pete Hansen offers his own self-described curmudgeonly critique in “Scientific, Political, and Religious Evolutions.” He ends with a bit of hope, which leads into the next piece, “Hans Island,” by Rolf Buschardt Christensen, about the peaceful resolution to a territorial dispute. Finally, we recognize those of the Church and Life community whom we hold in our hearts as they have recently departed this life, namely Ellen Utoft Bollesen Juhl and Hanna Broadbridge.

0 Comments

By PASTOR ANDRÉS ALBERTSEN

[email protected] Friday Morning Reflections at Danebod Folk Meeting, August 20, 2022 The Danish King Christian III mandated the conversion of all Danes to Lutheranism in 1536 (this is why I used to say that in my family we have been Lutherans since 1536) and instituted himself as the leader and protector of the new faith. King Frederick III introduced absolute monarchy in 1660 and formalized and heightened the sovereign authority of the king in the religious affairs. Absolutism lasted until 1849. Lutheranism was the obligatory religion, the Lutheran church was the state church, and the law of the church was part of the national law. In fact, there was no distinction between state and church. It was the king’s responsibility to ensure his subjects’ fidelity to the Lutheran Christian faith.1 Small groups of Catholics, Jews, and Huguenots did get permission to settle in Denmark, but it was under the condition that they would be loyal to the Danish king and not propagate their beliefs. Those groups were not considered Danish. They were only tolerated under special dispensations and within certain restrictions. Due to pietistic influence, compulsory confirmation was introduced in 1736, the year of bicentenary of the Reformation in Denmark. From then on, although the king had the authority to make some exceptions, baptism and confirmation in the Lutheran State Church would be synonymous with official Danish citizenship and legal adulthood status. The confirmation certificate, extended by the pastor of the corresponding local parish, in his capacity of civil servant, was the document that conferred the legal adulthood status. The exercise of any of the rights associated with being a legal adult required baptism and confirmation in the Lutheran State Church. Those rights included among others the rights to marry, to enter into contractual relationships, to enter a guild, to access a profession, to change the place of residence, to travel freely within the regions of the state, to receive an inheritance, to comply with the compulsory military service, to study at the university, and to access employment in the state bureaucracy.2 Every Dane (or at least one member of each household) had the obligation not only to attend church on Sundays and feast days but also to remain awake during the services. There were overseers provided with long sticks appointed to make sure that nobody fell asleep. If somebody dared to take a nap during the service, he or she was woken by the strokes of those overseers. The rule was easier to enforce in the countryside than in the towns and in the capital city, where residents could attend any parish church they wished, and therefore the pastors had a harder time keeping an eye on their parishioners.3 In the countryside it was, however, where most of the population lived (Eight out of ten residents lived in the countryside in Denmark in 1850),4 and peasants had to attend the parish of their place of residence. The pastor in the countryside was the only local symbol of the authority of the king and of the culture of the capital. Normally the pastor would be the only academically trained person in the parish, he would own the only library in the parish, and he would operate the biggest farm in the parish, the one assigned to the pastor in order to provide him with a good income. The farm was not the pastors’ only income though. The members of each parish had to pay tithe to the pastor, and the pastor charged a fee for performing baptisms, confirmations, weddings, and funerals.5 It is worth mentioning that the pastor, in his capacity of civil servant, carried out other duties as well (apart from the strictly pastoral duties). The pastor had to collect the taxes; take the censuses; help with the administration of the compulsory military service; record births, baptisms, deaths, weddings and confirmations in the parish register; supervise and inspect the local schools; encourage agricultural innovations; run the system of poor relief; and perform the vaccination against smallpox.6 And when, in 1841, the rural districts received the authority to govern themselves, the pastor was normally the one appointed to preside over the corresponding council. Meanwhile, in the Copenhagen area, clergymen would play leading roles in the Danish government and bureaucracy. The disempowerment of the Danish nobility brought about by the implementation of absolute monarchy in 1660 was an important factor in giving clergymen the position of prominence that they reached in the Danish society.7 The end of absolutism came with the approval of a constitution in 1849. The constitution guaranteed the right to freedom of religion and supposedly put an end to the connection between religion and civil rights in Denmark. In principle, no one would ever again be forced to become a member of a certain religious community nor be deprived of the full use of civil and political rights based on religion. Yet the Lutheran State Church, that up to that time had not had a legal corporate existence of its own, was transformed into the “Danish People’s Church.” The constitution stated that “the Evangelical Lutheran Church is the Danish People’s Church and as such is supported by the state,” with the understanding that the state could not disregard its responsibility for the spiritual needs of its people.8 The constitution also promised that a future law would codify and lay down the internal organization of the church and the mode of its relationship to the state. To the annoyance of some and the delight of others, the parliament never passed such a law (and never means even to this day of August 20, 2022). The promise of the constitution came to be interpreted instead as meaning that the church affairs would be settled by laws, on a case-by-case basis, passed in the parliament and administered by the minister for church affairs. And please pay attention to the fact that the minister for church affairs for many decades to come would be in charge of overseeing not only the church, but also the education, museums, the ballet and opera, and culture in general.9 It was as late as in 1933 that the church and the school system were separated. We also have to notice that in 1849 99.9% of the population were Lutherans. In spite of the approval of the 1849 Constitution, the organization of state and society in accord with the church went on as if nothing had changed. The way to become something in society was much easier if you were a good conforming Danish Lutheran.10 These were the conditions of what Kierkegaard calls Christendom: a Christian state, in a Christian nation, where everything was Christian and all were Christians where one saw, wherever one turned, nothing but Christians and Christianity. In Christendom, maybe even the nobler domestic animals and their offspring were Christians, Kierkegaard jokingly says, although he recommended the setting up of a committee composed of pastors and veterinarians to look further at the issue.11 Kierkegaard accused the Danish state of having employed 1000 officials (this was the total number of pastors in Denmark around 1850) who, in the name of proclaiming Christianity (and this was to Kierkegaard far more dangerous than a clear and open attempt to hinder Christianity), were financially interested in having people call themselves Christians-–the larger the flock of sheep taking the name “Christians” the better and in letting the matter rest there, so that they did not come to know what Christianity in truth is.12 To illustrate to what degree it was certain that everyone was and had to be Christian, Kierkegaard gives in 1855, six years after the approval of the constitution, the example of “an atheist who in the strongest terms declared all Christianity to be a lie,” and who “moreover, in the strongest terms declared he was not a Christian.” Even when it was against the law to state that Christianity was a lie, the author of the statement would have been considered a Christian anyway. As evidence, Kierkegaard imagines what would have happened if the atheist man died. As long as he left so much money that the pastor, the funeral director, and several others were each able to get their due, he would have been buried as a Christian. Only if he had left nothing (Kierkegaard says that “a little” would not have made any difference, because “the pastor, who is Christianly contented, is always contented with little when there is not more”), only if the man had left literally nothing—then attention might have been paid to his protests, since by being dead he would also have been prevented from corporally paying with physical labor the costs of being Christianly buried.13 “When Christianity entered the world, the task was to proclaim Christianity directly,” but “in ‘Christendom’ the relation is different,” says Kierkegaard. “What is found there is not Christianity but an enormous illusion,” and therefore “if Christianity is to be introduced here, then first and foremost the illusion must be removed. But since this illusion, this delusion, is that they are Christians, then it of course seems as if the introduction of Christianity would deprive people of Christianity. Yet this is the first thing that must be done; the illusion must go.”14 In spite of this negative view of the church, the pastor, and this system that he called Christendom, early in his life Kierkegaard decided that he would engage in the fascinating and hard task of a lifetime that it was in his view to become a Christian, and maybe in the process of figuring this out for himself he could help others ponder who they were and what they wanted to be. He earned the academic degree and the fulfilled all the other requirements to become a pastor in the Church of Denmark, but he intentionally decided not to get ordained. As a lay person, he thought, he would not be able to claim any other authority than the honesty and persuasiveness of what he said. “I am without authority; far be it from far be it from me to judge any person.”15 “I do not call myself a Christian; I do not speak of myself as a Christian,”16 Kierkegaard provokingly said. In the face of the hard task of a lifetime that it was to him to become a Christian, we are all lifelong learners. Kierkegaard also repeatedly said that he first talked to himself,17 and he invited his dear reader to read him aloud, if possible, and gain in this way the strongest impression that he or she would only have him or herself to consider. Kierkegaard knew that to be alone, and especially to dare to be alone with Christ’s demand and invitation is dreadful. It makes us aware of all the undefined possibilities of life;18 it compels us to make a choice, our own choice. The honesty of the choice—and we can never make our choice once and for all; we have to choose again and again—the honesty of the choice matters more than anything else to Kierkegaard. Nothing could be worse than the indifferentism of having a religion diluted and botched into sheer blather, in a passionless way.19 Preferable to that is to Kierkegaard the honesty of the humble admission that we cannot fully respond to the demands of Jesus Christ on our life, or the honesty of the plain acknowledgement that we do not want to be Christians,20 or even the honesty of the decisive, resolute, and definite choice of not wanting to have a religion.21 Please engage in a little thought experiment now with Kierkegaard and with me. It is a special way of thinking because Kierkegaard and I want you to think with the heart. (Remember The Little Prince’s secret, that “it is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.” Kierkegaard would agree). Imagine that you have never heard anything about Christianity. And now consider how many thoughts there are that could not have arisen in a human heart, but must have come from somewhere else. Kierkegaard is alluding to 1 Corinthians 2, where the apostle Paul claims that “God’s wisdom is hidden from normal human perception.”22 Kierkegaard provides a long list of thoughts that in his view could not have arisen in a human heart, and let me give you some of his examples: the thought that “the blessed god could need” the human being;23 the thought, referring to Jesus Christ, “that in order to make others rich one must oneself be poor;”24 the thought that God in Jesus Christ on “own initiative showed mercy upon the world;”25 the thought that it is God Godself who implants love in the human heart,26 and who commands us to love.27 My favorite example of a thought not arisen in a human heart that Kierkegaard gives is the story that he tells us through one of his pseudonyms, Anti-Climacus, in a book called The Sickness Unto Death about a poor day laborer and the mightiest emperor who ever lived. The poor day laborer had never dreamed that the emperor knew he existed, and he would consider himself indescribably favored just to be permitted to see the emperor once, and that would be something he would relate to his children and grandchildren as the most important event in his life. It turns out that this mightiest emperor suddenly seized on the idea of sending for the day laborer, not only so that the poor day laborer could have the opportunity of seeing the emperor once. No, the emperor sent for him and told him that he wanted him for a son-in-law. Yes, the mightiest emperor who ever lived wanted the poor day laborer to marry his daughter, the princess. What then? Quite humanly, the day laborer was more or less puzzled and embarrassed by it; he found it very strange and bizarre, something he would not dare tell to anyone, since he himself had already secretly concluded what his neighbors near and far would busily gossip about as soon as possible: that the emperor wanted to make a fool of him, make him a laughingstock of the whole city, that there would be cartoons of him in the newspapers, and that the story of his engagement to the emperor's daughter would be sold by the ballad peddlers. A little favor from the emperor would have made some sense, but this plan for him to become a son-in-law was far too much. The poor day laborer would never have dreamt of it; it was, here it comes, a thought that would never have arisen in his heart. Would he have the courage to believe it? Would he be offended? Or would he honestly and forthrightly confess that such a thing was too high for him, that he could not grasp it, that it was to him a piece of folly? Maybe you can imagine how Kierkegaard’s pseudonym continues the story. He does it by saying that this is exactly what Christianity is. Not only some of its aspects, but contrary to the rationalist understanding of Christianity, Christianity as a whole is something that could not have arisen in any human heart. Christianity as the teaching that every single individual human being, no matter whether man, woman, servant, girl, cabinet minister, merchant, barber, student, or whatever—this individual human being exists before God, this individual human being who perhaps would be proud of having spoken with the king once in his life, this human being who does not have the slightest illusion of being on intimate terms with this one or that one, this human being exists before God, and may speak with God any time he wants to, assured of being heard by God—in short, this person is invited to live on the most intimate terms with God! Furthermore, for this person’s sake, also for this very person’s sake, God comes to the world, allows Godself to be born, to suffer, to die, and this suffering God—this suffering God almost implores and beseeches this person to accept the help that is offered to him! Truly, if there is anything to lose one’s mind over, this is it! But will I have the humble courage to dare to believe or will I be offended?28 This invitation from God is not only a demand on our intellect, but on our whole way of living, and depending on the circumstances in which we receive the invitation, it can be an accusation, a message of comfort, and a call to repentance. By contradicting common sense in a radical way, Christianity is, and I agree with Kierkegaard, the invitation to live in a way that can indeed be appealing. I believe that we need to expose ourselves again and again to the astonishing claims Christianity makes and that are not obvious to anyone,29 that we must live up to our dignity as God’s chosen ones, holy and beloved. And you, you have to make your own choice. NOTES

|

Editor InformationBridget Lois Jensen Archives

March 2023

|

Subscribe | Gift |

Submit an Article |

Contact |

© COPYRIGHT 2019 CHURCH AND LIFE.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed