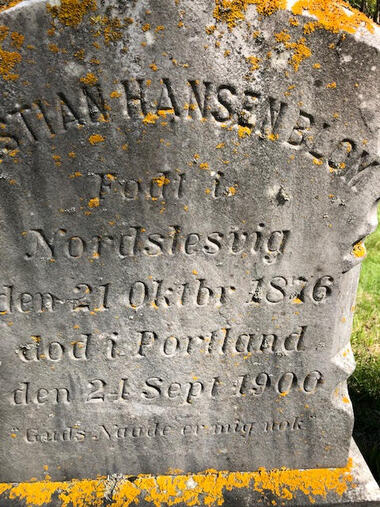

By THOMAS BLOM CHITTICK [email protected] Great-uncle Carl was troubled all his life with discomfort in an ear. According to family lore, a teacher had given him a terrible yank on his ear after he had simply asked for permission to go to the restroom. Why did he get his ear yanked? Because he had made his request in Danish. This was in the years after the second Danish-Prussian War of 1864, which Denmark had lost and in the losing, lost the Duchies of Holstein and Slesvig to Prussia. My great-uncle, his four brothers, and their sister (my grandmother) lived with their parents in the farming community of Fogderup, Ravsted Parish where Prussia engaged in an effort to Germanize the local people. Speaking Danish was not allowed. The largely Danish population of northern Slesvig waited patiently after the war for the enactment of a provision in the 1866 Peace of Prague whereby a plebiscite would allow residents of Slesvig to vote their national preference. It never happened. Prussia abrogated the provision in 1879. Uncle Carl’s ear may have hurt him all his life, I don’t know. But what I do know is that the Danish loss of Nord Slesvig hurt my Blom family deeply. They were fiercely Danish and the ear was an emblem of that pain, which lasted for a generation. With that portion of the treaty abrogated, the writing was on the wall for the elder Bloms. They could easily imagine their sons being required to serve in Bismarck’s army and they would have none of it. In 1893, the family immigrated to Portland, Maine. Many Danes immigrated from Nord Slesvig at this time, settling in communities throughout the United States. The pain for the Bloms continued. Another piece of family lore happened when a new pastor came to the Danish Lutheran Church in Portland. He was heard to have asked if the suffering under Prussian rule was really all that bad. In my hearing of this story, told in English, the teller always switched to Danish when giving the awful punch line, “Was it really that bad?” It seems the Danish truth of the insult by the pastor could only be felt in Danish! All that being said, the Bloms settled into Portland rather successfully, all the while keeping up interest in Nord Slesvig. Another uncle, Hans, wrote a pamphlet, De Danske Sønderjyder (The Danish Slesviggers), published by Dannevirkes Trykkeri in Cedar Falls, Iowa, that was a detailed study of the pro-Danish residents of all the districts and towns of northern Slesvig. My sense is that there was some form of political awareness or even pressure being expressed by Danes in the US after WWI for the treaty of Versailles to include a provision for a plebiscite to be mandated for Slesvig. One other piece of family lore that indicates how the Bloms settled into Portland and retained their Danish loyalties has to do with the day they, along with many other immigrants, stood before a judge to be sworn in as American citizens. As the story is told, the judge interrupted the proceedings to say that while they would all now be American citizens, they were never to stop being proud people of the nationalities of their birth homes. That really resonated with my Blom relatives, proud as they were of their Danish homeland. How different such warmth is compared to how immigrants are spoken to and thought of in parts of today’s USA. The Treaty of Versailles, signed in June 1919, did indeed provide for the hoped for and long delayed plebiscite in Slesvig. On February 10, 1920, the area from which the Bloms came voted themselves back into Denmark. All but my great-grandfather lived to see the day. A few years later, all the Bloms, including my dad and his brother, took a trip back to their homeland before finishing out their lives in Portland. Another uncle, Anton, would keep his Danish identity by attending a Folk School out in the western U.S. [probably in Solvang, CA - Ed.] My grandmother would similarly hone her Danish identity by attending a “finishing” or secretarial school in Copenhagen. But by the time of the plebiscite, all the Bloms where happy to be Danish Americans. Among the many headstones in the Blom burial section of the Pine Grove Cemetery north of Portland, the ones for the elder generation were inscribed in Danish. Still fiercely loyal to the land of their origin, instead of writing that they came from Denmark, it says they were born in Nord Slesvig! Typical of Scandinavians who love to sing and know many hymns from memory, one of the stones has the epitaph: Tænk naar engang (Think of the time), the first words of a line from a popular hymn, to which a Danish passerby would know the conclusion and say, “den taage er forsvuden” (when this fog shall disappear). I imagine it is in reference to St Paul’s “now we see as in a mirror dimly, but then face to face.” But I also imagine it has the double meaning of their sense of loss of homeland and hopes for its return to Denmark. What is more, I think how contemporary this sentiment is for today, the fog of virus and political bitterness rife in our time. When will this fog be lifted? On June 15, 1920, HM King Christian X rode by horse across the border of the land restored to Denmark. After centuries of conflict, the borders were fixed and the crowds who received him were exultant. His grand-daughter, HM Queen Margarethe II, was to have taken that same route by auto this June, but these plans were cancelled due to the coronavirus pandemic. Still, all of Denmark has marked this occasion with pride. And we of Danish heritage can join them from this side of history and this side of the Atlantic in reflecting upon the gifts to our American life all those immigrants brought to these shores.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Editor InformationBridget Lois Jensen Archives

March 2023

|

Subscribe | Gift |

Submit an Article |

Contact |

© COPYRIGHT 2019 CHURCH AND LIFE.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed